‘Where there is no vision,” the Bible tells us, “the people perish.” It’s a lesson absorbed by Sayon Hughes, son of an African-Caribbean pastor, the Bristol “yute” who is the ambitious protagonist of Moses McKenzie’s impressive debut, An Olive Grove in Ends.

But there’s a snag. Sayon’s admirable vision for social mobility – to escape the mean streets of Ends and buy a grand house overlooking the Avon Gorge – is predicated on him selling enough heroin to put down a substantial deposit on his dream home. And it’s further complicated by the little matter that our narrator observes after only a few pages: “Blue-and-white police tape cordoned off the footpath where I’d taken Cornell’s life not two days ago.”

Sayon is a killer. But he’s not on the run, because those who witness his stabbing of Cornell, a rival drug dealer, are either destined for an early death themselves or obey the local code of silence, an omertà that pervades Ends.

Early on, McKenzie offers a striking description of Sayon’s Ends, an impoverished multicultural neighbourhood in Bristol, close to St Paul’s, called Stapes or Stapleton Road. It is split in two by a carriageway: “The first part was mini-Mogadishu … the second (top side) was likkle Kingston.” Ends was where “once you arrived you only left when those in charge wanted to rebrand”. But Stapes is on the road to gentrification. “Seven years ago the only white people you saw had black children, dreads or drug addictions,” notes Sayon. Now he’s vexed because the community is being leeched by “proper-looking white people”.

The writing, resplendent with streetwise Jamaican-English, illuminates a gritty urban realism: alleys filled with used syringes among the detritus picked through by foxes; the coercion of teenagers by sexual predators who “lotion girls with newfound riches”. The novel, though, is as intellectually reflective as it is determined to show the young author’s raw bona fides. Many passages convey the cynicism of the adult residents: Sayon’s unforgiving mother “poured past relationships down the drain like a wino intent on betterment”; at a local Baptist church, the elders “earned their wisdom through a lifetime of mistakes” and took pleasure “in seeing their children falter as they had”.

McKenzie’s prose, especially the dialogue, wrestles with a conundrum: how to navigate the tension between instances where the language is heightened by a vernacular that lifts it above the ordinary, and the majority of exchanges, which have a soap-opera banality. It succeeds, largely, in being closer to The Wire than EastEnders, though at times the author betrays his inexperience by telegraphing future dramatic turning points, and through a tendency to keep on restating the constant jeopardy faced by Sayon.

At the heart of the novel is a love story between Sayon and Shona. Both are children of priests – one, Pastor Hughes, is the patriarch of an extended criminal family renowned for their violence, and the other, Pastor Lyle, though sceptical about his daughter’s boyfriend, is “a man who had dragged the darkness from his past”, and sees something of himself in Sayon. Pastor Lyle believes the yute is a candidate for compassion, even if his love for Shona will not cover the multitude of his sins. Sayon is also, believes his cousin Hakim – a proselytising Muslim – primed for religious conversion.

McKenzie depicts Sayon as a stand-in for the many young Black Britons whose trajectory propels them through a pipeline from school to exclusion to prison; Sayon is first excluded, not unreasonably, when he “floors a teacher”. But despite his tough exterior, he’s self-conscious in the presence of adults and worries about the impact of his sins, “an airborne contagion”, on others. Mostly unencumbered by a sense of guilt for Cornell’s murder, he’s weighed down by remorse over the plight of a cousin, Winnie, who overdosed on the “food” that Sayon sells.

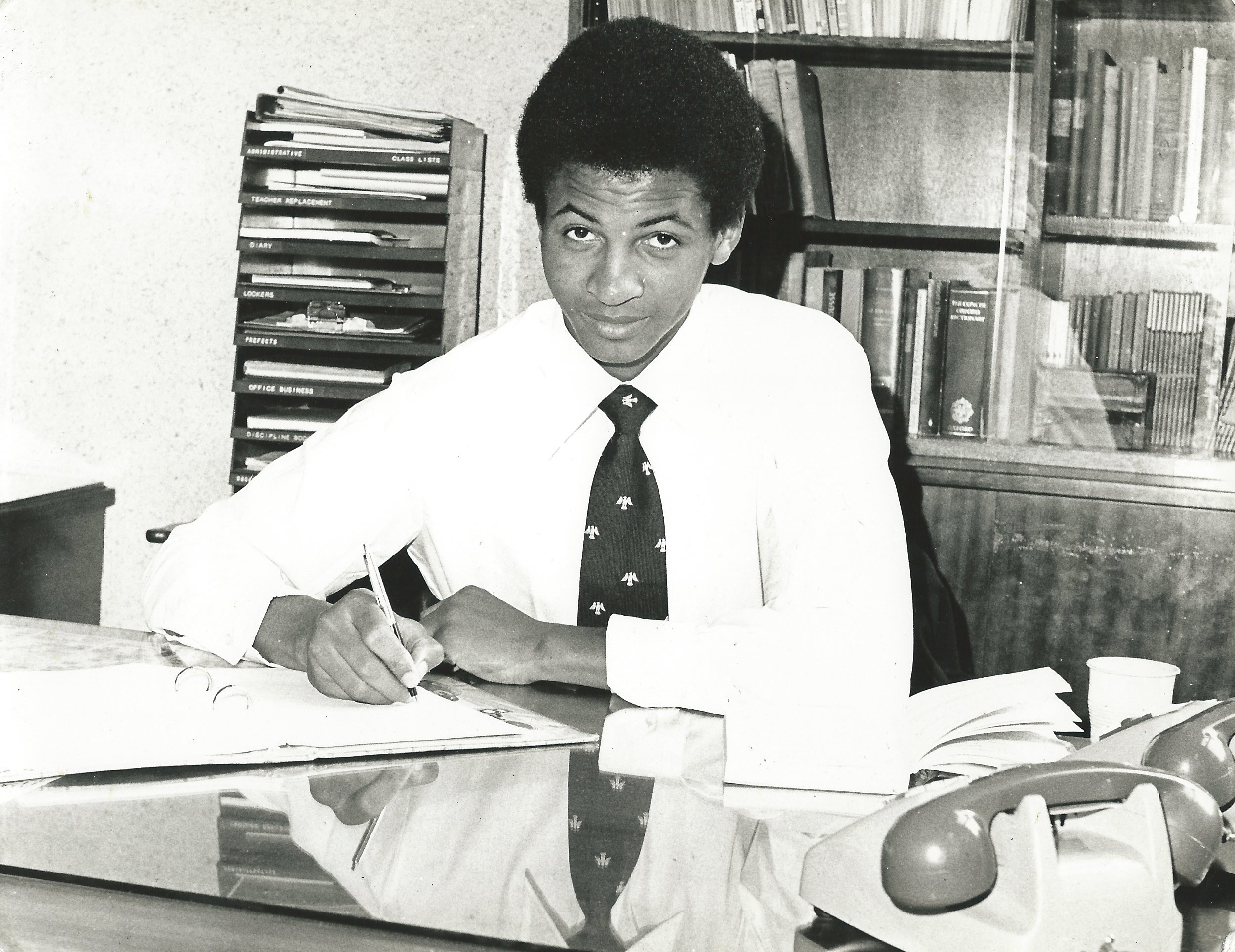

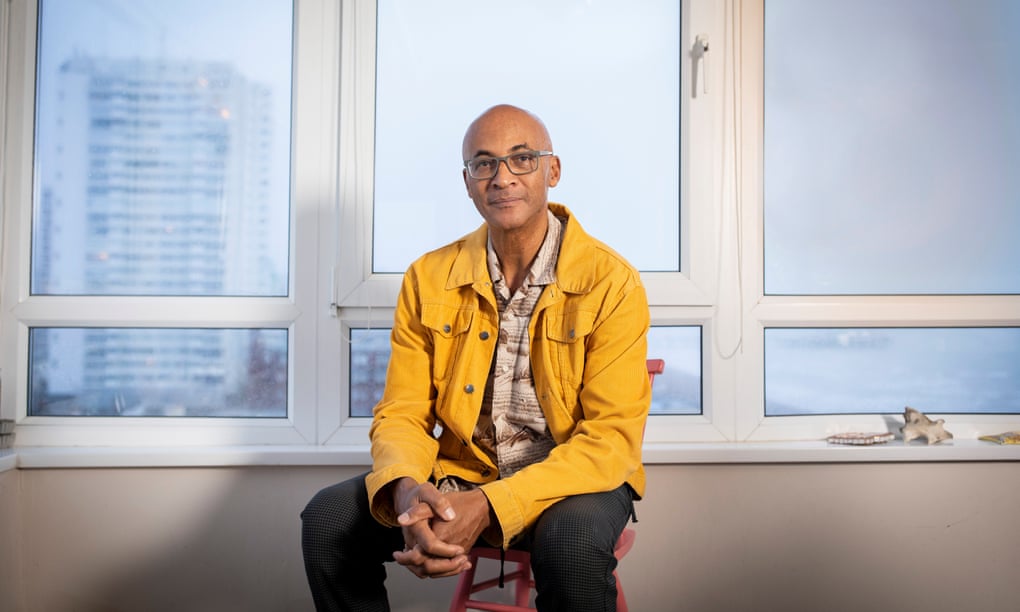

Ultimately An Olive Grove in Ends is a fable, peppered with biblical and Qur’anic epigraphs, and with Jamaican proverbs that inform its spiritual tone. Announcing the arrival of a promising 23-year-old author whose work is wise beyond his years, the novel is both a tale of redemption and a guide for how young, disaffected Black Britons – especially descendants of the enslaved – might, as Bob Marley advises, emancipate themselves from mental slavery.